After decades of declining populations, the rusty patched bumble bee receives a positive 90-day finding requesting the species be listed as "endangered".

Friday was a good day for the rusty patched bumble bee. After decades of declining populations and a nearly 90% contraction in range, it was given a glimmer of hope for a future: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a positive 90-day finding in response to an Endangered Species Act petition requesting listed as “endangered.” What this bureaucratic statement means is that the FWS agrees that there is evidence that the bumble bee is in trouble and that they will now take an official look at whether or not it deserves protection under the ESA. It’s a seemingly small step but hugely significant.

Gaining legal protection is a long process. Insects or other invertebrates are often given lesser priority compared with birds or mammals; a decade is considered swift for many struggling species. But success in getting a species protected — listed under the ESA as “threatened” or “endangered” — brings it great benefits, and can mean the difference between survival and extinction.

The Endangered Species Act, passed by Congress in 1973 and signed by President Nixon in December of that year, has been described as the broadest and most powerful wildlife protection act in U.S. history. Until it was passed, federal laws aimed at preserving species applied only to vertebrates. Passage of the ESA extended coverage to all plants and invertebrate animals, marking the first time that insects received specific federal protection in the United States.

The strength of the ESA lies in its capacity to influence the actions of both public agencies and private parties. Once a species has been listed, the ESA requires critical habitat to be designated and recovery plans to be written for most listed species. Funds can be provided for habitat acquisition by federal agencies and for conservation efforts by individual states, both of which have been a great help for insects with limited geographic distributions. In addition, the Act makes it illegal to “take” individuals of a listed species. To “take” is defined as to “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or attempt to engage in any such conduct.” (Limited taking of a species may occur, but only with a federal permit, and only for research purposes or as unintentional or “incidental” take as a result of other lawful activities.) The act also allows participation by the public in the determination of which species should be listed — the petition which initiates any listing process and then public comment periods at salient points in the process.

In a statement issued when he signed the ESA, President Nixon declared that “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the array of the animal life with which our country has been blessed. It is a many-faceted treasure, of value to scholars, scientists, and nature lovers alike, and it forms a vital part of the heritage we all share as Americans.” Unfortunately, if you read the media in recent months, you’d think that insects were treated differently. In Nebraska, people complain about money being wasted on protecting habitat for the Salt Creek tiger beetle. In Oklahoma, biologists surveying for the American burying beetle have been threatened at gunpoint. In Illinois, Hine’s emerald dragonfly is blamed for limiting a city’s water supply.

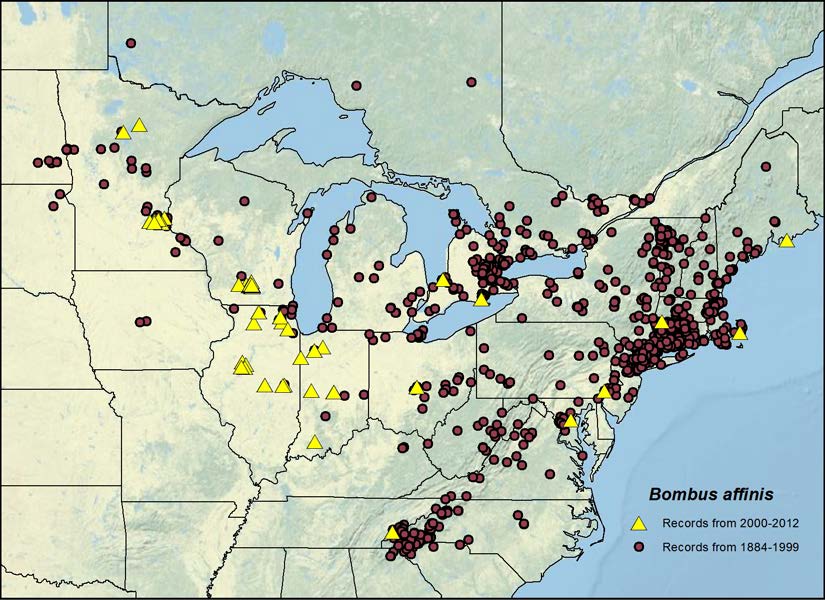

But back to the rusty patched bumble bee. The bumble bee faces numerous threats, including diseases, pesticides, habitat loss, and climate change. It is listed as Endangered under the Species at Risk Act in Canada and as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

Friday’s good news was in response to an ESA petition authored by Xerces staff and bumble bee scientists Dr. Robbin Thorp, professor emeritus at the University of California at Davis, and Elaine Evans, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Minnesota. The petition was submitted in January 2013. A 90-day finding should, as the name implies, be issued after 90 days. This one took 960, and required the combined efforts of the Xerces Society and the Natural Resources Defense Council to nudge the FWS into issuing it. The next step is for the FWS to conduct a status review and issue a 12-month finding. I sincerely hope that this is completed on time. A long delay may sound the death knell for this beautiful and valuable pollinator.