Given their muted colors, erroneous reputation as pests, and the nocturnal nature of many species, most people fail to take notice of moths — let alone celebrate them. Enter National Moth Week. National Moth Week was started by moth-minded scientists and environmentalists in 2011 as a citizen science project celebrating moths and biodiversity. “Moth-ers” of all ages and abilities are encouraged to learn about, observe, and document moths in their backyards, parks, and neighborhoods. We encourage you to check out the list of events on the National Moth Week website and join in!

Moths Vs. Butterflies – What’s the Difference?

Both butterflies and moths belong to the order Lepidoptera, however many are surprised to learn that moth species outnumber butterflies significantly. In North America there are 800 species of butterflies and just over 11,000 species of moths. Although the rules for distinguishing moths from butterflies are not hard and fast, moths generally differ from butterflies in some key ways:

Wings – When at rest, butterflies typically hold their wings upright or open, whereas moths typically rest with their wings either spread or folded back over their abdomen.

Antennae – Butterflies typically have segmented club-tipped antennae, whereas moths frequently have broader, feathery or comb-shaped antennae. can often be beautiful and intricate structures in and of themselves.

Caterpillars and cocoons – Butterfly caterpillars are typically smooth, some with defensive coloration and patterns mimicking snakes. Moth caterpillars are often elaborate, with hairy bodies or multi-spiked protrusions (some butterfly caterpillars have spikes, too). Both butterflies and moths undergo complete metamorphosis, transitioning from a caterpillar to an adult. To do this, butterflies form a chrysalis, which is actually the hardened skin of the caterpillar in its final pupal stage. Moths form cocoons, which are external structures spun from silk, often incorporating plant material or hair from their own bodies.

Behavior – Butterflies are active during the day, whereas most species of moths are active at night, or during dawn and dusk. But this is not always the case!

Moths on the Day Shift

While the majority of moths are nocturnal, many fascinating day-flying moths may be observed. Sphinx and hawk moths (family Sphingidae) may often be found visiting beebalm and morning glory in gardens. Often confused with hummingbirds, sphinx and hawk moths are some of the fastest flying insects, with some species capable of flying more than 30 miles per hour! Their coloration ranges from dusky drab camouflage to bee-mimicking yellow and gold, to exotic colors that mimic hummingbirds. Unlike butterflies and other moth species, these moths can hover in place while drinking nectar from flowers with their exceptionally long probosci.

Other day-flying moths include wasp mimics such as the red-shouldered ctenucha moth (Ctenucha rubroscapus)and the currant borer moth (Synanthedon tipuliformis), with slender bodies and bright warning colors.

If you’re lucky enough to spot them, the cecropia silk moth (Hyalophora cecropia) and the luna moth (Actias luna)are some of the more elaborately decorated moths. Both are active around dusk near woodland edges.

Observing Moths After-Dark

Night time is the right time for spotting many moth species. We’re likely all familiar with spotting moths swatting against a porch or street light. In fact, such light-pollution may be causing real harm to these nocturnal insects. If your goal, however, is to get an up-close-and-personal look at moths, here are two time-tested methods to help out:

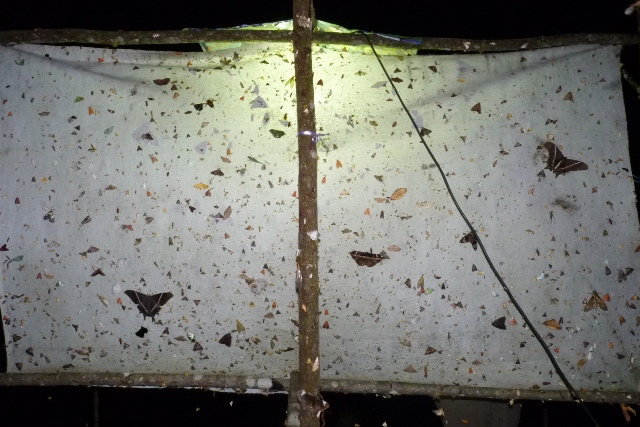

Make a light trap: Drape a white sheet over an overhead tree branch or something similar. Tie ends of the sheet to posts or other fixed points to create a flat, taut surface like the sail of a ship. Steadily shine a stationary bright light to illuminate the entire sheet. Moths (and other nocturnal insects) will be attracted to the light and flutter against the sheet without being harmed. Try to get some photos of the moths who come to visit and upload them to the National Moth Week site or Moth Photographer’s Group to help identify and document your findings. When you’re through, turn off the light to allow your moths to get on with their nighttime business.

Put on the red light: Place a red lens over a flashlight and use it to investigate insect activity on various plants. This is an especially good way to explore not just moths, but many other interesting nocturnal insects at all levels.

Gardening for Moths

Common wisdom has it that moths visit night-blooming plants with flowers that are typically white or pale in color such as angel’s trumpet (Datura spp), moonflower (Ipomoea alba), and common evening primrose (Oenothera biennis). While there is certainly some truth in this, the relationships between moths and plants is much more complex. Some moths do not feed as adults, so it is critical to recognize and protect their larval host plants. For moths that do feed as adults, sugar sources such as flower nectar, rotting fruit, and certain tree saps are needed.

Like butterflies, nectar-feeding moths that are active during the day are likely to visit many of the wildflowers you may already be planting for butterflies. They prefer to feed from long, showy, tubular flowers. The flower preferences of night-flying and dusk/dawn active moths are less well known. We know that these species are often extremely important pollinators of night-blooming plants since other pollinators are generally inactive at night.

In creating a moth-friendly garden, your focus should generally be on following the same protocols we recommend for other types of pollinator-friendly habitat. Provide an abundant selection of native flowering plants, provide host plants for caterpillars, create shelter in the form of leaf litter or small piles of brush and branches, and protect all pollinators from pesticides. For more information about gardening for moths, check out our book Gardening for Butterflies, which includes moth-specific plant lists by region and more information about moth conservation.