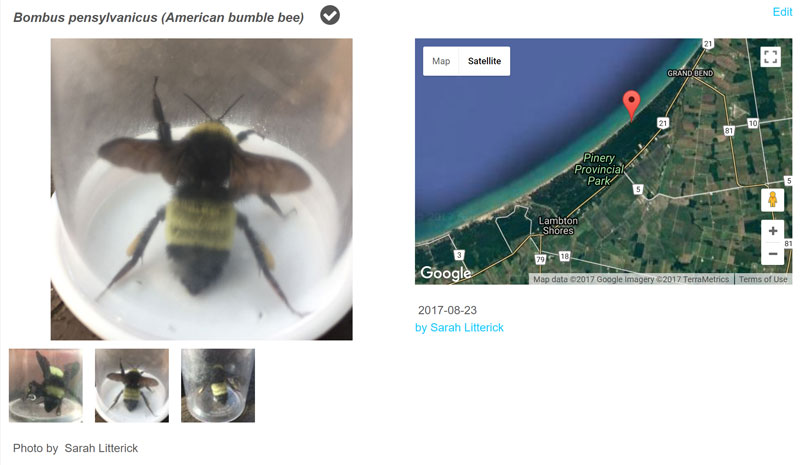

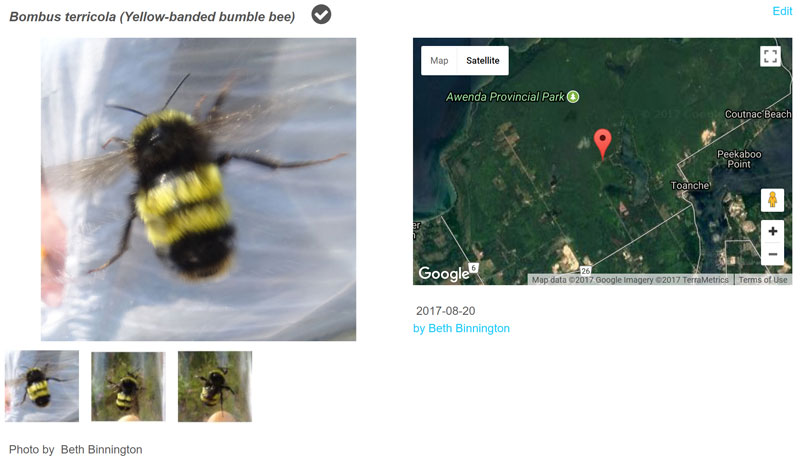

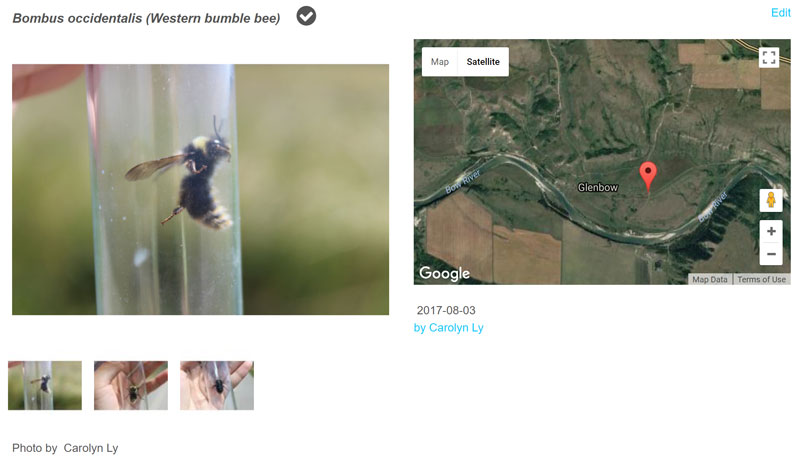

There are 40 different species of native bumble bee in Canada, and evidence suggests that up to a third of them are currently in decline. One of the most extreme examples of decline is the rusty-patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis). Formerly among the most common species across its range, it is now officially listed as endangered in both Canada and the United States. Other declining species include the yellow-banded bumble bee (B. terricola), the western bumble bee (B. occidentalis), and the parasitic gypsy cuckoo bumble bee (B. bohemicus). In addition, several other species may now be experiencing declines in portions of their ranges, including the American bumble bee (B. pensylvanicus) and the yellow bumble bee (B. fervidus).

Tracking populations of so many species is a time-consuming task. Surveys by professional research staff are often limited by personnel availability and funding support. By harnessing the power and energy of volunteers to supplement these efforts, citizen science programs can “fill in the gaps,” increasing the geographic reach and contributing valuable data. With this in mind, Wildlife Preservation Canada’s Native Pollinator Initiative has implemented a Bumble Bee Watch citizen science survey training program. This survey program engages citizen scientists in bumble bee conservation by teaching them the same survey techniques that professional researchers use, and encouraging them to locate and monitor rare and declining bumble bee species.

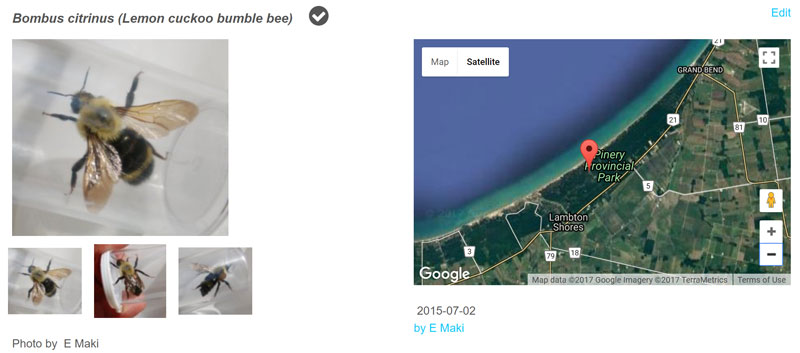

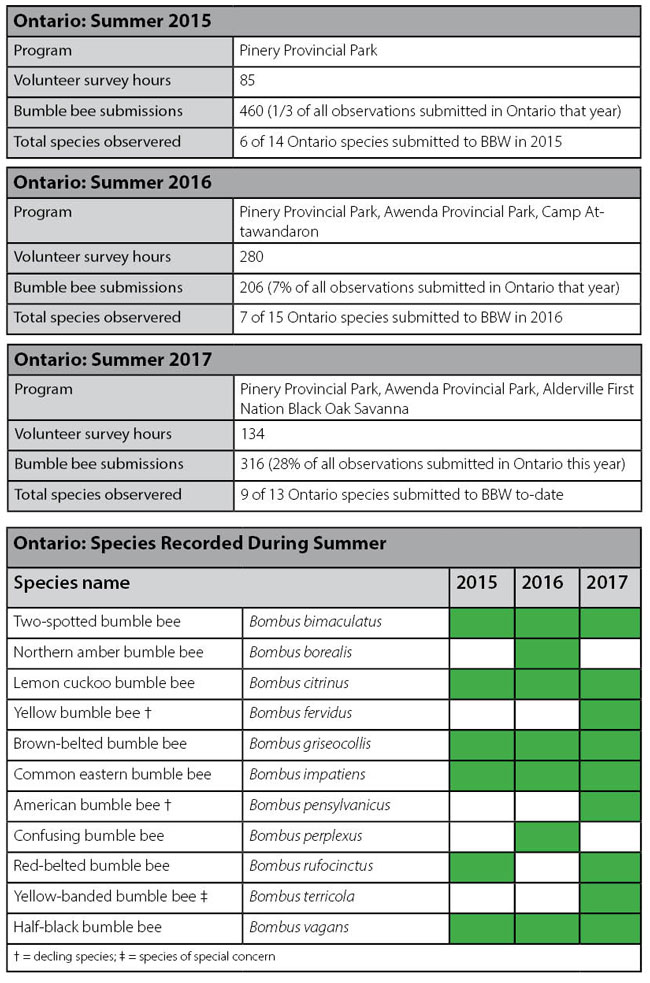

Begun in 2015 at one location—Pinery Provincial Park near Grand Bend, Ontario—Wildlife Preservation Canada has expanded these citizen science training programs to multiple locations across Canada. The programs are held in areas with historical observations of at-risk species.

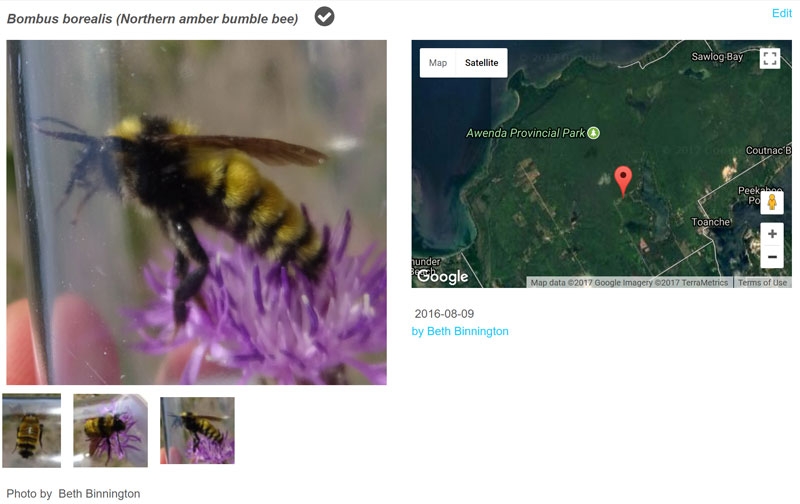

Pinery Provincial Park, for example, is notable as the last known home of the rusty-patched bumble bee in Canada (it was observed in 2009), and the last place where the gypsy cuckoo bumble bee was seen in any of the provinces (in 2008, though there are several records from the Yukon and Northwest Territories as recently as 2017). Of the two training locations added in 2016, Camp Attawandaron is a scout camp bordering Pinery Provincial Park, near the rusty-patched territory. The other new venue, Awenda Provincial Park in Tiny, Ontario, has a historic (1988) observation of the gypsy cuckoo bumble bee. WPC staff have surveyed there every year since 2013, frequently recording observations of the yellow-banded bumble bee.

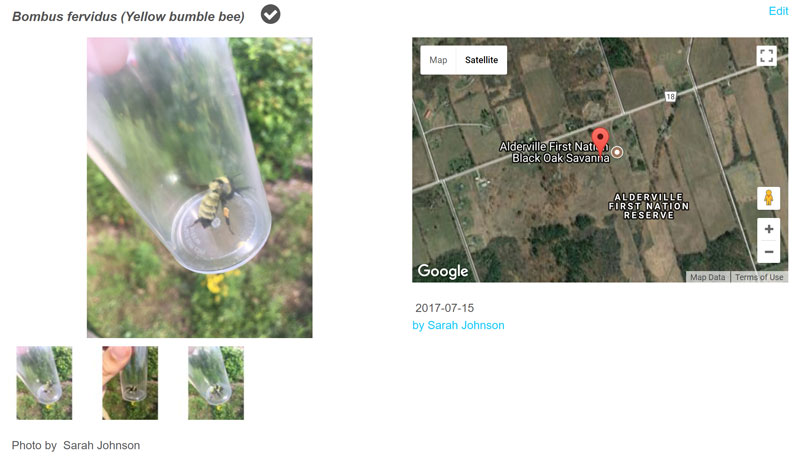

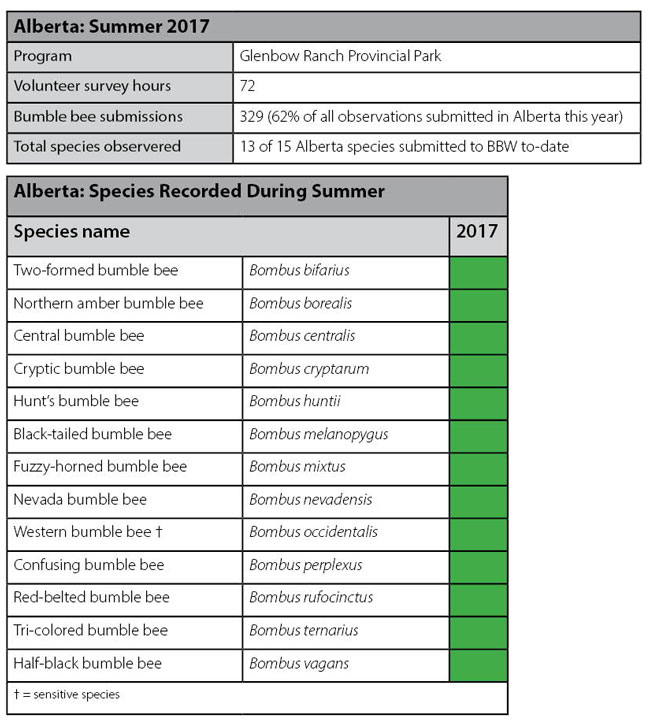

In 2017, we added programs at Alderville First Nation Black Oak Savanna in Roseneath, Ontario, and at Glenbow Ranch Provincial Park near Calgary, Alberta. Both sites support at-risk bumble bees: Alderville has records of the American and yellow bumble bees and there was a confirmed sighting of the western bumble bee at Glenbow in 2014.

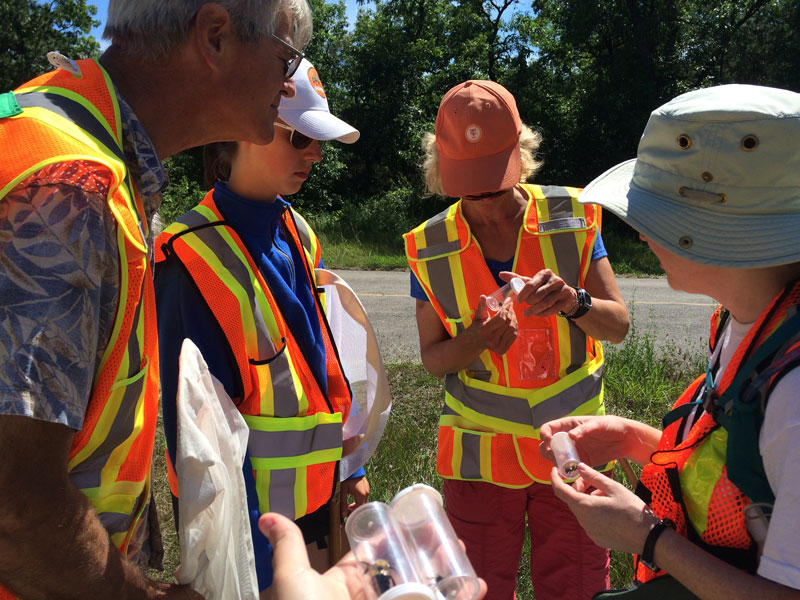

Volunteer training workshops are held in early summer each year to educate prospective citizen scientists on survey protocol. The workshops include a presentation component covering topics on bumble bee biology and identification, threats to bumble bees, and ways citizens can help. This is followed by a hands-on training session that gives volunteers the opportunity to implement the survey protocol by collecting and photographing bumble bees. All volunteers are provided with a training package that includes survey instructions, site maps and data sheets, a local bumble bee identification cheat-sheet, and a variety of other educational and outreach materials.

Volunteer surveys are typically between 30 minutes and 2 hours, on days where the chance of rain is less than 30% and the temperature is between 15° and 35°C. At the beginning of each field day, volunteers collect the necessary materials for their survey from a locked storage bench on-site, before making their way to their selected survey location. Once there, they’ll identify the best patches of flowers, and attempt to locate and photograph bumble bees on flowers, or collect them using insect nets and place them temporarily in vials for easier viewing. All bees are released after identification. At the end of each survey, volunteers return all equipment and materials to the storage bench, and submit observations to BumbleBeeWatch.org.

The goal of the program at each location is to give volunteers the necessary skills and access to all required equipment, so that they can come back regularly over the summer and survey independently for bumble bees. This not only builds a clearer picture of the bumble bee populations at each site, but also contributes to the ever-growing database at BumbleBeeWatch.org. Citizen scientists now have the opportunity to use a variety of platforms to submit their bumble bee observations – as of summer 2017, the free Bumble Bee Watch app for iPhone and iPad has streamlined the contribution of bumble bee records across North America!

Volunteer participation in these hands-on training programs has made a HUGE impact for bumble bee monitoring in key areas for species at risk in Canada. Summaries of the findings from the WPC Native Pollinator Initiative Bumble Bee Watch citizen science surveys at the program locations are given below. All the data that have been contributed through citizen scientist efforts continues to be invaluable to bumble bee researchers and policy makers across the country.

If you are interested in getting some hands-on training in catching, identifying, and recording important data on bumble bees in Canada, stay tuned! Keep your eyes open for opportunities to sign up for bumble bee survey training programs in your area. WPC will be running programs near Calgary, Alberta, and in multiple locations in Ontario in early spring of 2018. In the U.S., watch out for new initiatives in Washington, Idaho, and Oregon.

Notable Observations